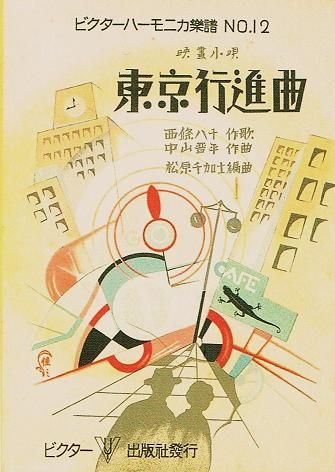

It was May 1929 and a film hit Japanese screens as a kind of declaration of modernity. Kenji Mizoguchi, today recognized as a pioneering filmmaker in Japan, premiered his work “Tokyo March” (also known as “Life in Tokyo”). Although it was a silent film (there were still a few years before the arrival of talkies), the song of the same name performed by Chiyako Sato and composed by Shinpei Nakayama that accompanied the film, reflected in its lyrics a Japanese capital in boiling waters and going through profound social changes as an echo of the country’s opening in the mid-19th century. A specific style was mentioned in the lyrics of the song as part of that strong Western influence that was felt in the city: jazz.

Emerging in the south of the United States at the end of the 19th century, jazz was one of the musical genres that entered a Japan whose popular music, until then, was mostly linked to folklore and the entertainment of the lower classes in tune. with cultural expressions such as kabuki theater or puppet theater (bunraku).

Little by little, it generated a large number of followers and led to the emergence of the “moga” and the “mobo” (contraction of modern girl y modern boy, respectively), young people who embodied fashion and the new lifestyle in this modern pre-war Japan. Ginza and Asakusa soon became the Tokyo areas of choice for strolling and enjoying these new protagonists. Meanwhile, Japanese society viewed these new trends with suspicion and a heated debate arose about the loss of Confucian family tradition and the desire of these young people to embrace and consume new things, as a kind of liberation from the roles of yesteryear.

However, as Japan entered its most militaristic period in the 1930s, jazz began to be associated as part of the American “enemy” and, therefore, was harshly censored (that small void would soon be filled by the tango that unites Argentines and Japanese so much today, but that is another story). It would not be until the end of World War II that jazz would return within a package that now included other popular genres of the time such as country, rockabilly and boogie-woogie.

These musical styles would be promoted – among other cultural products associated with Western democracy – by the North American Occupation government, which wanted to erase any trace of Japanese nationalism. In any case, beyond this intentional dissemination with a political objective, the truth was that the American soldiers themselves stationed at the bases were eager to consume said entertainment. And Japanese musicians were willing to provide it, given the scarcity of other types of jobs in the first years after the war.

Amid all these discussions and political upheavals, the yazu the cat (jazz cafes) looked for a way to flourish (and sometimes survive) as spaces for the enjoyment of the genre. They weren’t conventional coffee shops: they were places to lose yourself in the music and leave the busy conversation in the very distant background. “Chigusa Jazz Kissa”, founded in 1933 in Yokohama, and considered the oldest and best preserved, closed its doors in 2022, but functions as a museum that seeks to highlight the importance of jazz in the cultural life of the Japanese.

Jazz bars were also added to the jazz kissa, creating a vibrant, extremely intimate and unique atmosphere in Japan for those who like the genre. It could be said that there is no large city in Japan that does not have several of these establishments, today highly appreciated by foreigners looking for alternative tourism experiences. In addition to having a large collection of records by world jazz artists, some venues offer regular performances by local artists. Beyond the economic and political ups and downs of recent decades, data from 2021 estimated the existence of about 100 jazz bars and cafes still open in Tokyo.

For several years, some jazz critics pointed out that Japan had done little more than directly imitate jazz coming from the United States. It is true that, during the postwar American occupation, learning the styles and copying them perfectly ensured precious employment in times of scarcity and reconstruction. However, artists such as Muraoka Minoru (1923-2014) or Yamamoto Hōzan (1937-2014) demonstrated over time that Japan could contribute to the genre by adding traditional elements to the typical sound of jazz. In this way, local instruments such as the flute shakuhachi They managed to carve out a place that seemed reserved only for pianos, double basses, trumpets or drums.

The continuous changes in the consumption and preferences of new generations represent an additional challenge for the long-term survival of spaces as particular as cafes and jazz bars. Meanwhile, it is also well worth taking an afternoon and evening on your next visit to Japan to enjoy this particular universe that has actively collaborated in building the rich Japanese musical culture.

Graduate in Oriental Studies (University of Salvador). She is a Public Relations specialist. She has a higher diploma in Education, Images and Media (Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences). She has a Master’s Degree in Cultural Industries, Politics and Management (National University of Quilmes). She is a professor of the class on Japan in the subject Intercultural Processes, of the Master’s Degree in Cultural Diversity (National University of Tres de Febrero). She teaches training courses on the history, culture and protocol of China, Korea and Japan (Isaac Fernández Blanco Museum of Hispanic American Art).

Source: https://reporteasia.com/cultura/2024/04/30/dia-internacional-jazz-japon-genero-parte-integral-cultura-musical-moderna/