The Western fascination with the Far East is ancient. It dates back to the 16th and 17th centuries, when European traders began to bring Chinese porcelain and Japanese lacquers from their travels. Chinese porcelain, which surprised Europeans with its technique and decoration, began to be adapted in China to Western tastes and became such a standard that the word “china” still stands for porcelain in English today.

The development of steam navigation and railways in the transition between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century facilitated communications and, consequently, cultural and material exchanges with other parts of the globe. We then witnessed a true “craze” for the art and customs of the Far East, societies in which the most ritualized and symbolic models of life contrasted with the industrial hustle and bustle that was experienced in Europe.

It was at this time that Calouste Gulbenkian was seduced by the charms of the arts produced in China and Japan, acquiring for his collection, between 1907 and 1947, a set of exquisite objects, made in porcelain, lacquer and hard stones, but also some textiles, or woodcuts on paper.

Like what happened with European art, also with regard to Chinese ceramics, Gulbenkian was particularly interested in pieces from the 18th century. They correspond to the period of the Qing dynasty, in which China was governed by the Manchu tribe, originally from Northeast Manchuria, whose emperors were great patrons of the arts, which provided a great boost to artistic production. But the collection also includes examples from other periods and dynasties, such as a cup from the Yuan dynasty, from the beginning of the 14th century, or a blue and white porcelain plate from the Ming dynasty, from the beginning of the 15th century.

Cup with foot. China, early 14th century, Yuan dynasty. Porcelain with “qingbai” glaze. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum. Photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

The first is a piece just 10 cm high, very rare, covered in a translucent aqua blue glaze called “qingbai”, where Buddhist figures are represented in openwork panels. The Ming dynasty plate, the oldest example of this type in the collection, is a deep plate decorated in cobalt blue underglaze, with motifs that are part of the Chinese floral lexicon, such as the peony or the lotus flower.

Despite the historical and even cultural importance of Chinese porcelain, one of the most fascinating works from this nucleus belongs to another artistic category. This is the imposing “Coromandel” screen, produced in China at the end of the 17th century and exported to Europe through the coastal area of southeastern India with that name, Coromandel. A screen with 12 pine wood leaves, articulated by hinges, which was created as a gift for a high-ranking local dignitary on his fiftieth birthday, with scenes from his daily life. It is, therefore, not a screen produced for export, like others, which makes it rarer and more unique, allowing us a closer look at the life of Chinese high society at this time.

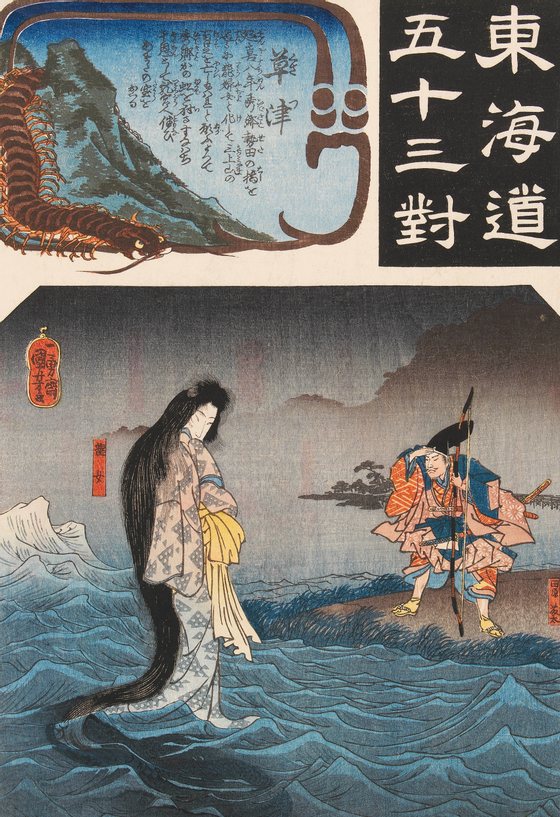

From Japan, Calouste Gulbenkian brought together a remarkable set of works, including prints by artists such as Utamaro, Hiroshige or Hokusai, among others, which evoke ephemeral pleasures, or the “floating world” (ukiyo-e) and lacquer objects, of refined execution, in which nature deserves a prominent place.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Kunisada e Utagawa Hiroshige, “Kusatsu”, da série “Cinquenta e Três Pares ao Longo da Estrada do Tōkaidō” [Tōkaidō goj ūsan tsui]. Japan, 1845. Print on paper. Editor: Kojimaya Jūbei, Ibaya Senzaburō, Ibaya Kyūbei, Enshūya Matabei, Ebiya Rinnosuke and Iseya Ichiemon. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum. Photo: Catarina Gomes Ferreira

Source: https://observador.pt/especiais/historias-de-arte-na-china-e-japao/